Features

Centralised

assumptions

The benefit of centralising assumptions

Assumptions are always centralised so someone wanting to flex the model can find the elements they want to change easily.

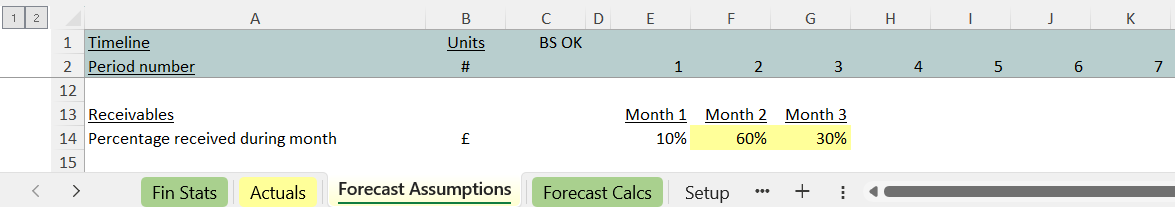

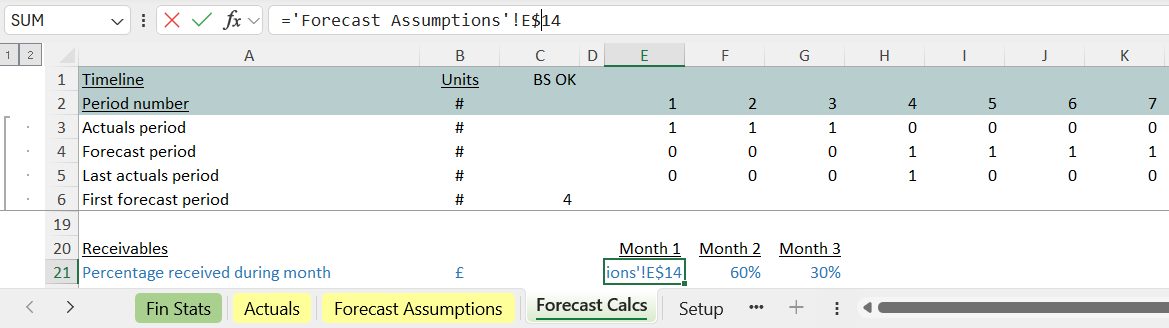

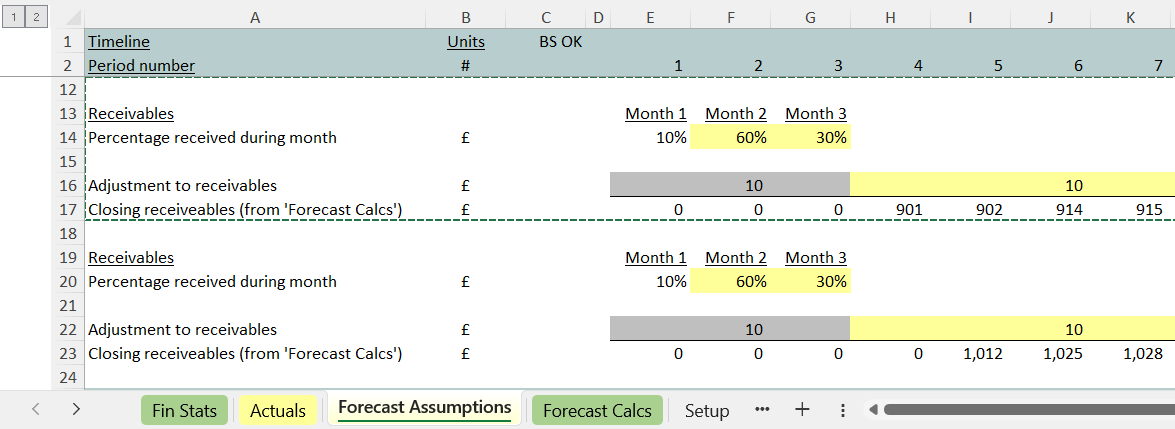

Notice below just these key assumptions for receivables. Notice they’re easy to find because they’re:

- positioned on the ‘Assumptions’ tab, along with other input assumptions

- given their own shading (yellow in this example).

Yellow cells always contain ‘hard-coded’ inputs. No other cells in the model ever contain hard-codes.

On the assumptions tab the receivables inputs are positioned after the preceding balance sheet inputs and before the inputs for the next line item.

The ‘flow’ matches (the layout of the line items on the ‘Fin Stats’ tab matches that of the layout on the ‘Assumptions’ tab, which matches the order of the calculations on the green calculations tabs.

In a large model that’s designed to help someone more easily find the section they want to look at or modify.

The benefit of importing assumptions

It’s easy for assumptions to become sprinkled around a large model (and harder to find), because it seems sensible to position an input next to its workings.

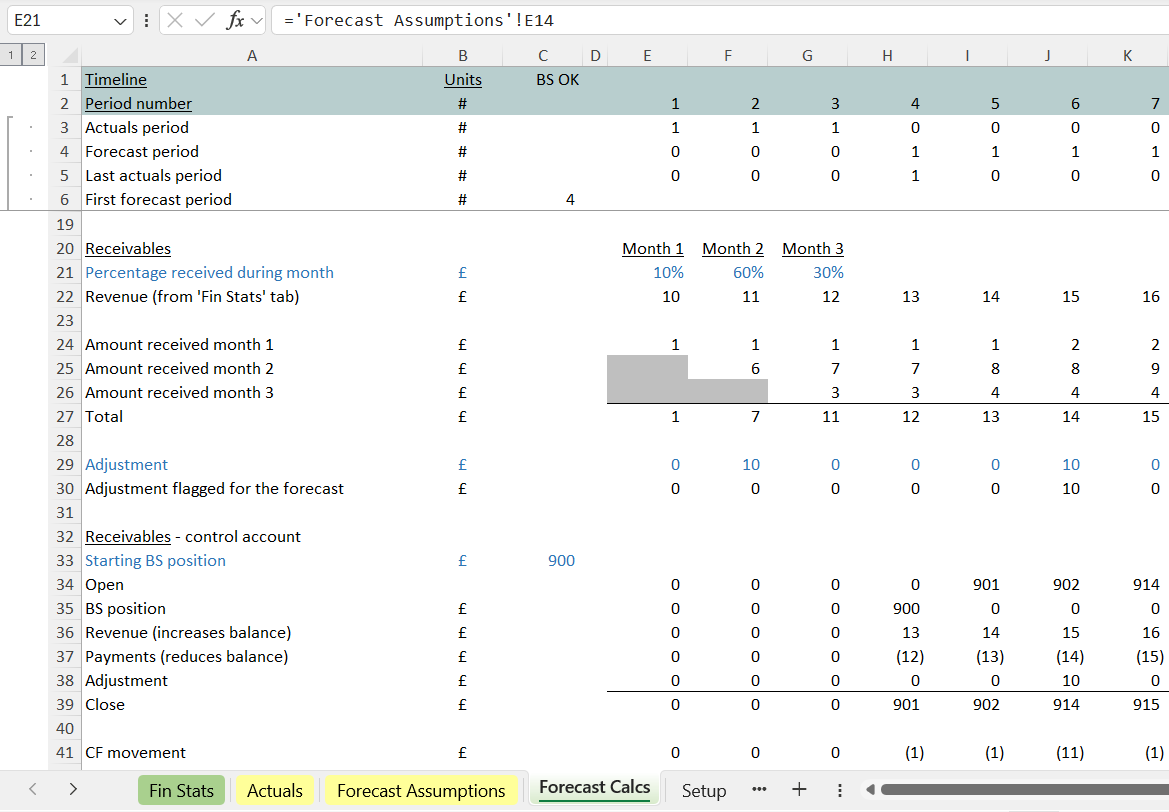

Notice the blue figures, which are a simple link back to the assumptions tab, where we’re positioning the input figure ahead of the next immediate calculations.

We’re positioning the input figure where it needs to be for the model workings, but the yellow-shaded figures that someone might want to vary are still successfully centralised on the assumptions tab.

If someone is reviewing the workings and wants to vary an input, they can alight on a blue cell, and make use of Excel’s “Ctrl [“ shortcut (that shortcut involves pressing the control key and, while holding it down, pressing the left square bracket “[“ key) to immediately trace back to the yellow cell on the inputs page.

The act of importing the input into the workings in blue as a straight-forward link (itself colour coded) makes it easy to jump back into the assumptions tab and find the assumptions cell you want to vary.

How importing helps the build progress robustly

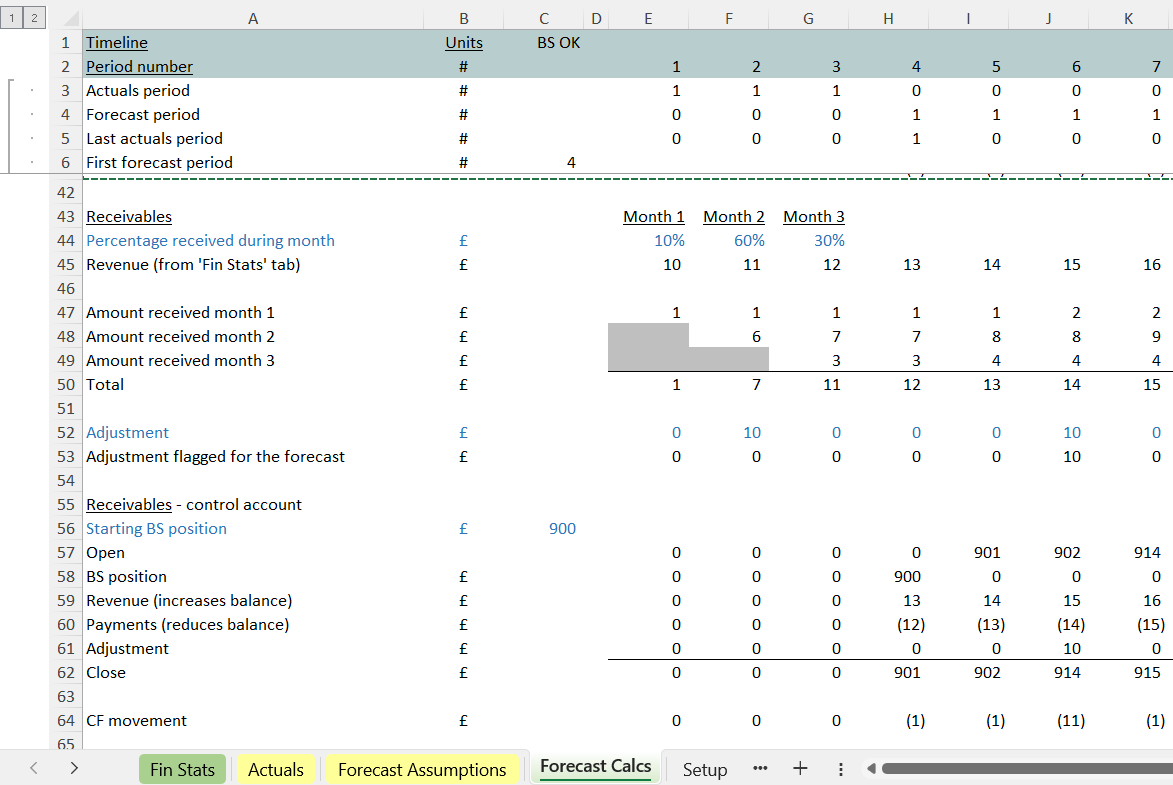

The receivables section is complete in our model. It’s pretty-much self contained.

Numbers flowing into the section from other parts of the model tend to be marked in blue.

At the bottom, as is usual for a balance sheet line item, we can find what’s flowing out. Line 39 at the bottom ends up on the balance sheet and line 41 arrives up on the cash flow statement.

Imagine we had a next section to build that had some similarities to this one. Perhaps we want to model a second receivables balance that relates to one particular area of our business. Perhaps we want to model payables (where, instead of thinking about how quickly we will get paid by customers, we are now thinking about how quickly we will need to pay suppliers).

Step 1: row lock the blue import cells

As a first step in building a next section, rather than creating that from scratch, we can make use of the existing work.

We can ‘row lock’ the blue cells (step 1) so that a $ dollar sign appears next to the row number.

Step 2: copy the assumptions down

Once the blue cells are row-locked, we can flick to the assumptions and make a copy of those.

Step 3: copy the calculations down for the new section

Next, we can move back to the receivables calculation and take a complete copy of those.

Remember the section is self contained, so it should stay working, nothing broken.

Step 4: rewire the imports

At this point the new calculations section contains blue cells wired to wrong place. Because all the cells are all shaded blue, it becomes easy to identify what to re-wire. In the new section we now know we need to go through all the blue cells re-wiring them to the new assumptions section created at step 2.

Finally we need to go through the entire section, checking for anything else that needs to be modified, and making sure the results for the section (the balance sheet amount and the cash flow) are wired into the financial statements.

Importing assumptions helps make the build process safer

What we’ve described above is a safer way of building a new model section:

- we look for the opportunity to make use of the work we did previously

- because it’s self-contained, much of the re-wiring required is limited to the blue import cells, reducing the chance we’ll make a mistake

- because we’re not rebuilding the new section completely from blank Excel cells, it reduces the chance of a mistake

- because we’re hoping to reuse the model’s calculation sections where we can, there ends up being similarities between sections that are solving similar challenges. As one section gets proven, tested and modified, the changes that result from that process can more quickly be applied into other sections that are similar.

What we do is combine importing with a practice of looking to re-use model sections, copying down a prior section to create new workings. A proportion of the work involved is limited simply to re-wiring the blue cells for a new section.

Importing assumptions helps make models better

Our practice of importing makes it easier to trace back to the assumptions you want to vary (the blue cells always remain highly-visible within the model’s workings).

At the same time we look for opportunities to reuse sections, and limit some of the work to the straight-forward task of re-linking the blue imports, reducing the chance of error.

It’s a build process that’s, by design, more robust – founded on the strict separation of assumptions.