The top 5 things you might want to look at when an Excel model hits your desk

Maybe like you, I’m regularly asked to look at others’ Excel forecasting work. Often there’s no large time allowance to pore all over the spreadsheet. So, in a short amount of time, I’ve realised there’s some things ahead of others I end up looking at. My aim is to get a quick feel for the work. Here are the 5 things I’ll look to assess it on to start.

1. Modelling for revenue

What I’m really looking for is a clear separation inputs -> calculations -> outputs. Are inputs collected up on one tab? Are they easily identifiable? Have they been given their own colour shading? Alternatively, are they sprinkled throughout and a little hard to find.

I’ll start at the top with revenue, seeing whether I can trace that through, starting with its inputs (can I see what I’d need to change to flex sales up or down?). But I’ll end up noticing modelling for costs as well.

I know this sounds like a basic thing but I’m regularly in receipt of work that just hasn’t done a perfect job of this. Looking to see how well assumptions are isolated tells me whether I’m on to a potential winner or not, from the start.

2. Modelling for receivables

When I’m looking at revenue at step (1) what I’m really looking for is separation of assumptions, and I end up noticing other driver-based modelling as well. Similarly here at step (2) when I say “receivables” what I’m really testing for is how (in fact, it ends up being ‘whether’) working capital is dealt with in the model. Testing the receivables lines gives me a first reading as to whether working capital is being dealt with at all well. More often than not, it’s not – so this becomes a big part of my mini test.

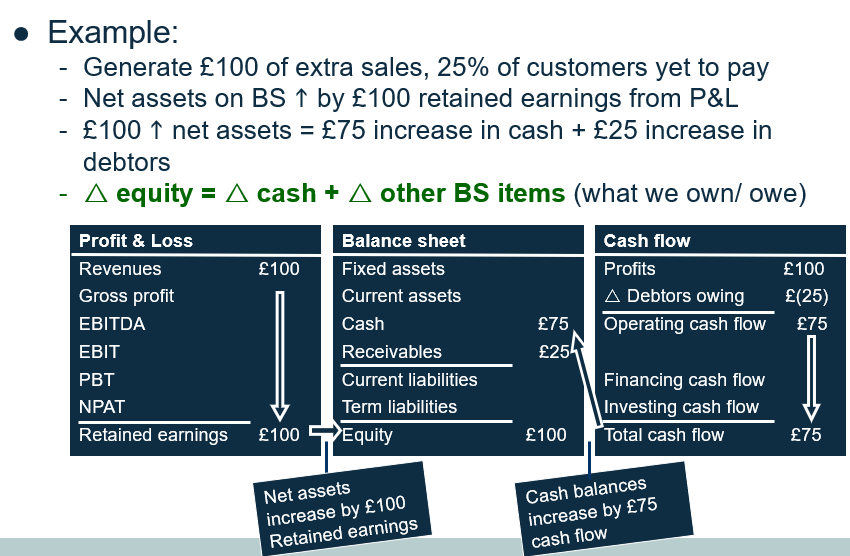

This is important. At (1) we were wondering how easy it might be to see an assumption that would help us flex sales up and down. Here at (2) we’re wondering whether the downstream cash flow impacts of that change in revenue are going to affect cash flow. If we’re flexing revenue so that we’re doing more business with more customers, we’re going to end up waiting for more customers to pay.

With receivables I’m just looking to see that the balance is being modelled using some sort of (sensible) mechanism I’ve seen before – rather that a creative novel surprise that’s new to me. Imagine you had a business that was doing £120m of revenue a year and there’s a nice isolated assumption in the model that sets receivable days to 30, with the receivables balance forecast at £10m (one month’s sales). If I find nicely isolated revenue assumptions in the model, could I (just for fun) double revenue to £240m and watch receivables jump to £20m? It’s that kind of dynamic I’m looking for (and, using the £120m or £240m revenue x 30 rec days / 360 days in a year, the mechanism doesn’t have to be complicated to make some attempt at accommodating that in the model’s calculations).

Yes I know there’s not 360 days in a year, but neither are there 30 days in every month. People use these kind of numbers sometimes to keep things simple.

Many models I pick up will quickly fail on the working capital modelling, so it becomes another quick and important test for me. It may not be attempted but often, when it is, there’s some convoluted complicated mechanism that I can barely trace or gain quick confidence in. The revenue x 30/ 360 dynamic might be rough and ready but because it’s easy to understand I reckon it’s less likely to see someone using the model to fool themselves or others into thinking there is no working capital or working capital will sit at 30 or whatever days without budging forever.

3. Is there a proper balance sheet check?

I’ve picked up plenty of models that just miss some balance sheet movements. They’ve left them out (VAT, tax, the delay between people working for us and being paid, staff bonuses that are going to become due). It would be better if they had been left out in the interests of simplifying. But most of the time when items are missing I think they’ve just been forgotten.

It’s easy enough to do. The model might be running profits and EBITDA. Then it might be starting with EBITDA and adding balance sheet movements to get to cash flow. At that point you’re free to totally forget about some of the usual balance sheet movements that might absorb cash.

However if, as part of your work, you had laid out a separate balance sheet (and included the regular line items in there as per your management accounts) it’s going to be harder to miss the cash flow impact of all the movements. Still, it can be done. If EBITDA + balance sheet movements = cash flow, despite listing the line items in a separate balance sheet component of your model, you could just leave some out.

So, when calculating balance sheet equity one way (assets less liabilities = equity on the model’s balance sheet) I’d like to see it also calculated a 2nd way. With a check that the two match. And no fudge factors in a remote line that contain the mysterious amount that forces the match, or some circular logic that does the same thing, or some white font shaded number off screen somewhere (I’ve seen it all).

Because this year’s equity = last year’s equity plus this year’s bottom-line profits (or retained earnings) we have a ready-made way of checking that we’re not fooling ourselves that it’s all there when we look up the balance sheet.

Here you can read more about the (few) steps a model needs to have in place (to construct that critically important #2 reading on the balance sheet). That properly constructed balance sheet check is there for a reason – to check that the x3 financial statements are talking to each other properly, and that the impact of all of the balance sheet movements is felt in cash flow.

Many of the models I pick up do something strange or unexpected here.

4. Could someone run a stress test?

If (1), (2) and (3) are a pass, (4) will already be a pass too. Thinking about this won’t take long now – it’s what we’ve been aiming for so far really. If assumptions have been isolated it’s going to be easy to do something to ramp up revenue in the model. If working capital is being modelled sensibly, working capital balances will change by the right kind of magnitude and proportion. And then, if at (3) the financial statements are talking to each other properly, there won’t be any strange ‘fudge factors’ in there and a stress test look like it will likely run through just fine.

Some models fail on (1). Lots fail on (2) & (3). Which altogether means that plenty of forecasts make it difficult or impossible for your investor or bank to do what they really want with the forecast (flex it), in the interests of making the internal recommendation for supplying finance to your business.

5. Is there anything else?

By this point (if many models are not making (1), (2) & (3) really easy for us) I’ve had plenty of time to surf around the model and notice a few things that might be ‘triggering’ me. I reckon modelling, as much as anything, is about recognising some rules are going to apply, putting those in place, and sticking to them religously. So, if there are things on-the-face-of-it-minor (like random formats, a vast array of neon colours employed haphazardly throughout), or a few more things that could-be-minor could-be-major (like unexplained circular references, long formulas that are hard to trace) I’ll start wondering whether this is the work of a rule-keeper and I may even start wondering whether it’s the work of someone who knows what the rules should be.

Really, it's been about the stress test

With a bit of time just focussing on (1), (2) & (3) – really trying to understand whether it’s a piece of work someone external to the business could run a stress test through – and surfing through noticing a few other things, my comfort levels will end up being somewhere in the range of quite low to nice and high.

The good news is, by focussing on a few high level mechanisms you’d want a model to have, it doesn’t need to take a long time to get a feel for whether what you’ve got on your hands could be mostly-good or a potential problem child!