Adjusting your deal balance sheet

Adjusting your model’s balance sheet need not be difficult, if (and it’s quite a big if) you’ve invested in a couple of smart features in your model structure.

1. A model that rolls forward at the flick of a switch

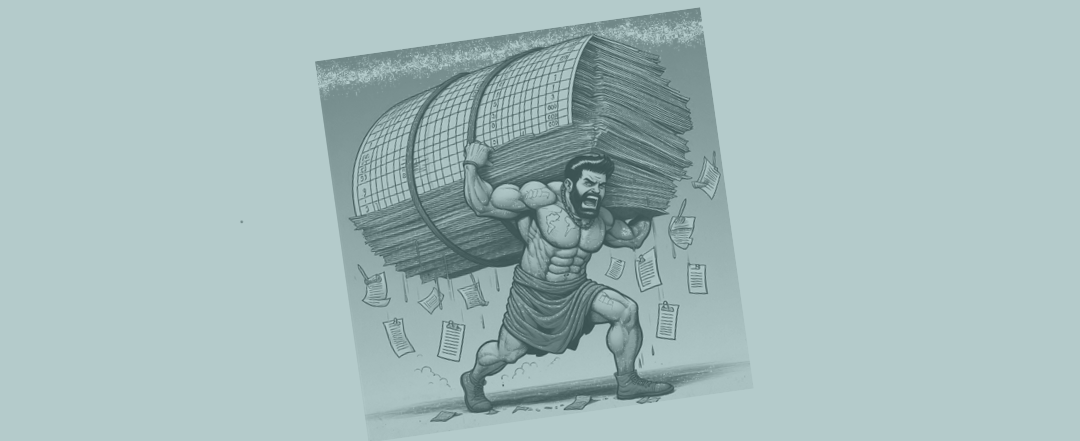

Here’s some detail on a structure where the model composes its financial statements from a ‘sandwich’ of actuals and forecast numbers, making the model easier to update.

As next month’s forecast becomes this month’s actuals, all you need to do is advance the model forecast start date by one month.

That opens up space in the actuals layer for the current month actuals. The forecast stays functioning as it was (subject now perhaps to a quick review that considers whether your outlook for the remaining months of the year has changed at all).

The new year-to-date forecast arrives, as it did before, as a composite of YTD actuals (with one extra month actuals added now) plus the forecast for the rest of the year.

It’s all much better than the alternative of writing over forecast formulas in lots of different places of the model, risking forgetting to change something that really should have been changed.

2. A model with a balance sheet that really balances

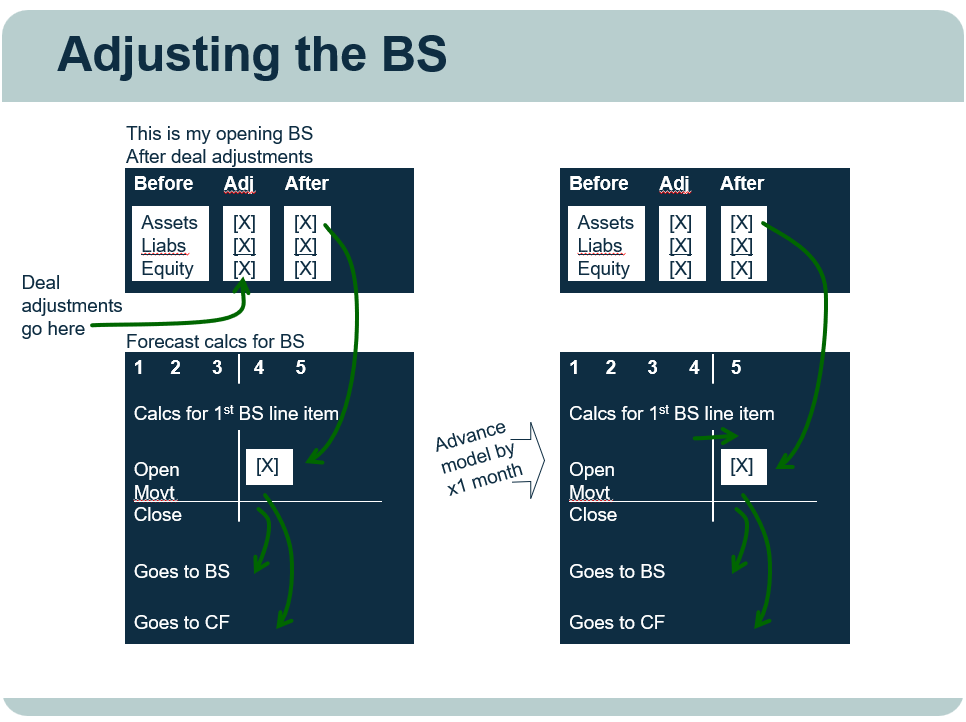

Here’s an outline of a model structure that sees your forecast start from an opening balance sheet that stays balancing when you keep building and add extra lines into your model.

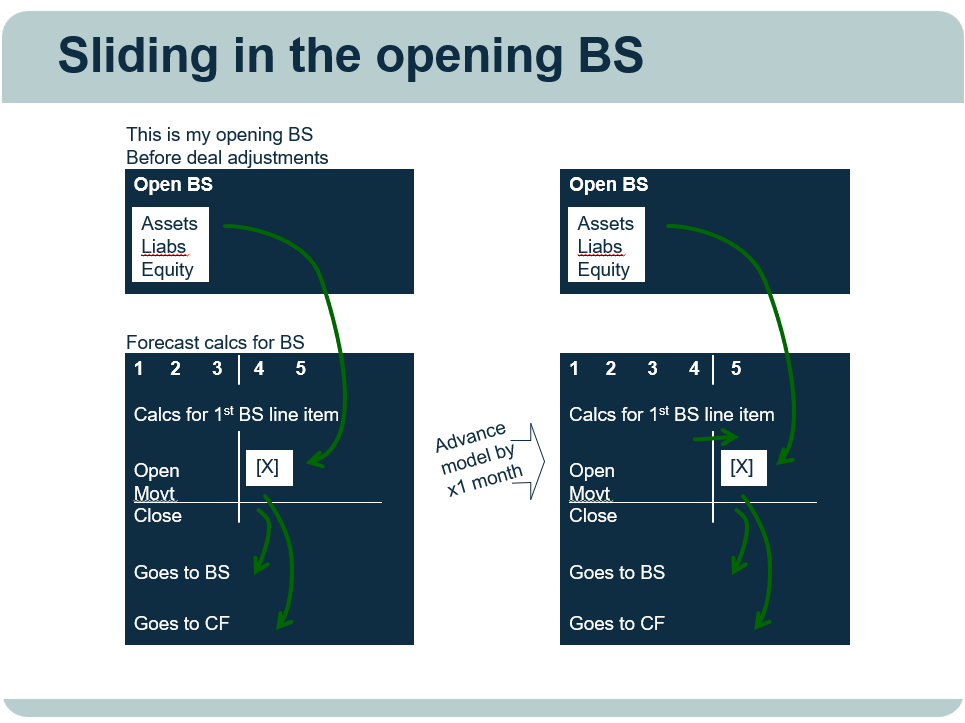

As described above, imagine advancing the model by one month, opening up room for new actuals. And imagine also the structure slotting the new opening – and balancing – balance sheet into place (one month further on than it was before).

It all gets quite neat and powerful and saves a lot of error-tracking headaches.

Where we’re at with our model structure right now

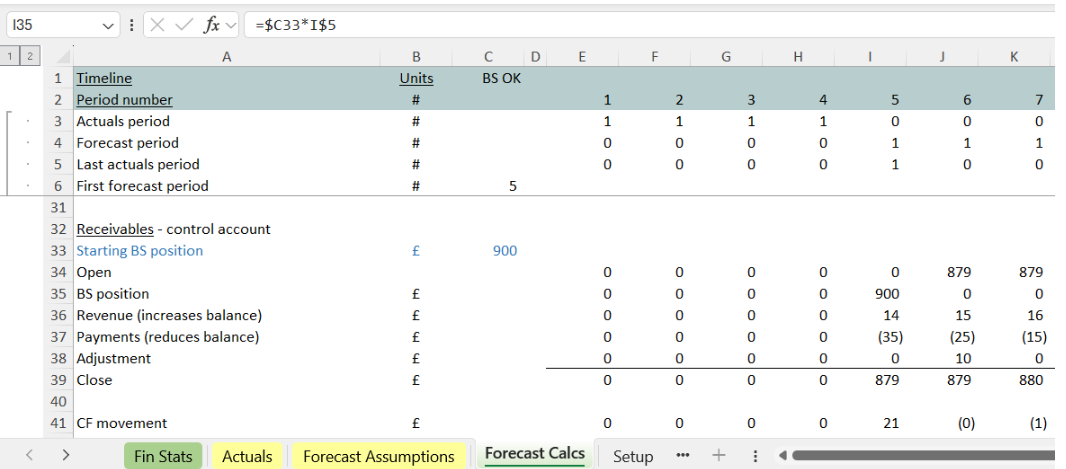

At this point, after steps 1&2 above, we’ve got a model that picks up the latest opening balance sheet (whatever that looks like) and automatically slots that opening position as the starting point for forecasting balance sheet movements and cash flow. See cell I35 in the example below. That’s a great place to be in.

Imagine you’re buying a business. The latest company accounts say one thing about the balance sheet, but you’ve agreed some adjustments to the accounts that affect what you expect to inherit:

- maybe there are some loans that the company has made to directors that will be cleared in advance of the transaction

- maybe certain amounts will be left in the hands of the previous owners, or reviewed and adjusted as part of a deal completion mechanism.

All of this becomes very easy to manage when you’ve invested in a design where the opening balance sheet is fed into the start of the forecast (without it, with lots of ‘fixed’ numbers in the wrong place, it becomes very awkward, painful and prone to error). All you need to do is slot in an ‘adjustments’ column as illustrated at the top of the diagram below.

Adjusting the balance sheet for something unusual becomes easy. As long as you’ve been able to think ahead with your design, and have taken the trouble to work with a structure that slots in the opening balance sheet as the start point for the forecast.