Setting up Excel scenarios so you can change them at the flick of a switch

Right at the end of a model build you might suddenly decide that you’d like to run some sets of assumptions (say base, high and low cases) through your spreadsheet.

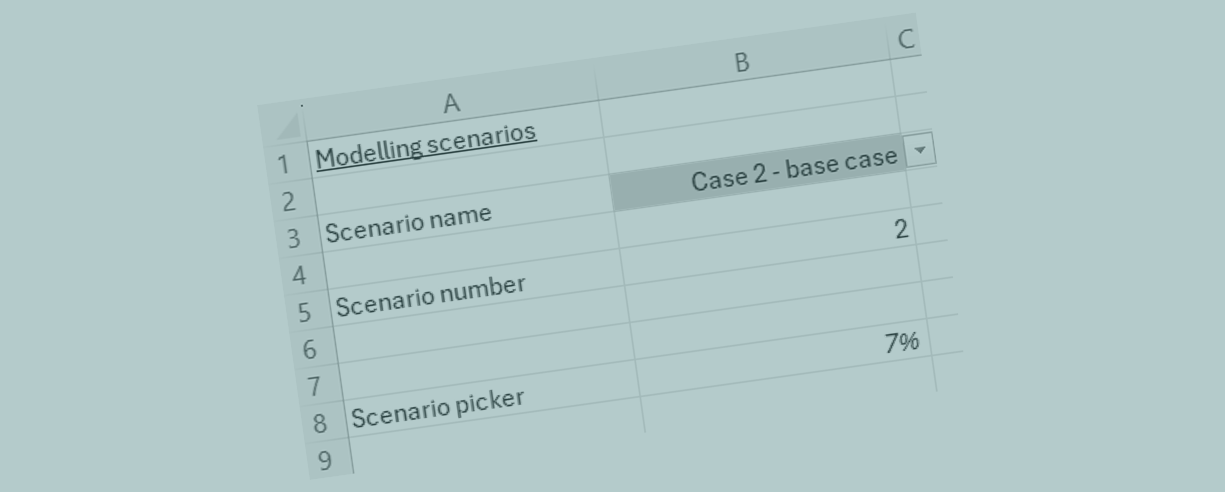

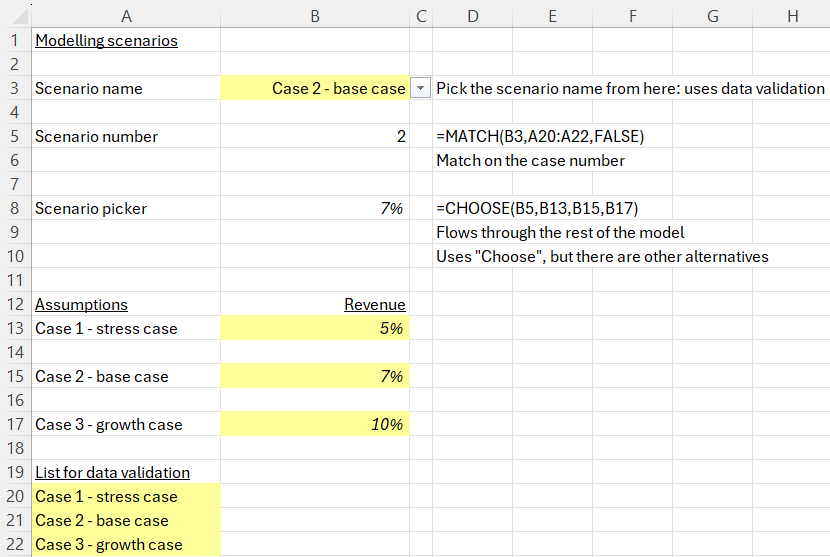

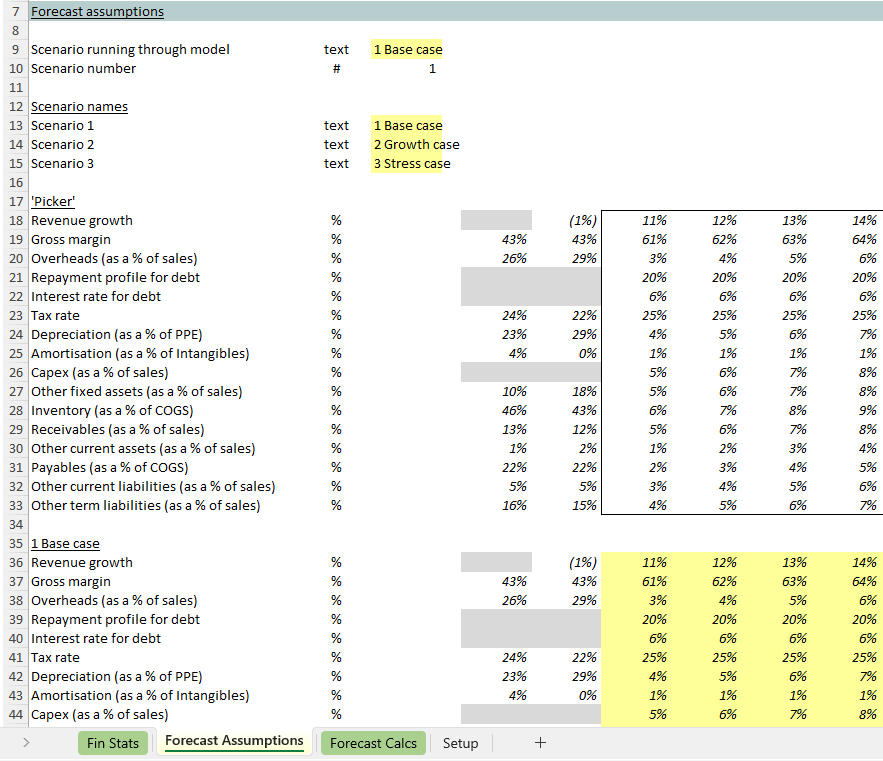

Here’s a small mock-up of a structure that could help you do that.

You can see some imaginary assumptions (you are going to have more than that, stretching down and across the page) stored from row 13.

Running assumption sets through an Excel financial model

The structure enables someone to flick between scenarios at cell B3. That cell uses data validation to create a drop down box that allows you to change scenario.

The formula at cell B8 pulls the correct assumption into place, which then gets fired through the rest of the model. The flow for the model is Assumptions -> B8 ‘Scenario picker’ (which pulls from the assumptions based on the case selected in B3) and then from B8 onwards into the rest of the model’s calculations.

We’ve used Excel’s “Choose” function in B8, but there are plenty of other alternatives if you prefer (such as XLookup).

Notice also the role of the “Match” function at B5, which becomes an input for what’s going on in B8.

Completing the final part of a build can all happen relatively quickly at the end. You create the drop-down box at B3, copy the assumptions down the page from row 13, create the ‘picker’ area at line 8 and then it’s pretty-much done.

However, although creating the switching can be pretty short and snappy (which becomes a super-valuable feature, because it allows you to sense-check your model outputs over a range of assumptions) there are a few tricks which mean you stand a chance of leaping over the small switching hurdle quickly.

(1) Clustering assumptions

The full model needs to be careful to cluster the assumptions that you expect to vary closely together. When it’s a set of line items for a set of time periods (imagine cell B13 above extending across and down the page) it becomes easier to pick all the flexing assumptions up and copy them down the page into lines 15 and 17.

Clustering the flexing-assumptions makes it easier to create a bigger version of the ‘scenario picker’ (at B8 in the screenshot above, and in rows 18-33 in the bigger example below).

Thinking carefully, from the start, about how to lay out the first go at assumptions (while you build the first draft of the model) becomes really helpful when you suddenly want to start flexing sets of things.

If assumptions are spread through the model, or even just spread too far apart in the assumptions tab, it makes it more difficult to flex blocks of numbers suddenly.

(2) The importance of having the financial statements working together in the right way

Here we can imagine an example where you know you are interested in flexing revenue growth. But you’ll probably be interested in flexing lots of other things as well, including costs.

For now though, let’s just concentrate on the revenue flex. If revenue is expected to grow, we’re going to expect the costs of supplying extra products to grow. Admin costs could grow. The balance sheet, working capital and cash flows could be further impacted. If the business sells more products to more customers, balance sheet receivables (amounts reflecting the fact that we have to wait for customers to pay us) will grow. Funding requirements will change. In the short term (if there’s a lag between manufacturing, selling and getting paid) funding requirements could go up, as could interest costs. The tax charge will change.

To contemplate flexing sets of assumptions through a model you have to be confident that the downstream knock-on impacts from any number you flex are reflected elsewhere in the profit and loss statement and in the balance sheet, so that the full cash flow impacts of the change are felt in the model.

That’s why you’ll spend most of your time building a model with the right links in place, so that the cash flow impacts of balance sheet changes are reflected in the model (with the balance sheet always balancing), while also being careful to lay out assumptions in a helpful way. It’s that forethought – paying close attention to what’s being built, and how it’s being built – that pays off when you are trying to accommodate that last-minute challenge: “Do you think we could maybe run a few alternative scenarios here?”.

Otherwise, perhaps with (1) assumptions spread in awkward places (requiring numbers to be collected up and the model restructured), and with (2) downstream balance sheet impacts not modelled in a way that links them to their upstream drivers, it could be a big job that’s required – needing to rebuild the model so that it can handle the impact of alternative input-sets.

It’s one of those cases where attention to design-detail from the start (thinking about the objectives for the model ahead of time) provides potential dividends – say when you want to conduct an exercise that looks at how far the business could stray off its base case assumptions before cash flow changes significantly.

As always, it’s always much better to conduct your modelling work preparing for what’s likely to lie ahead!